THEOLOGY OF DIGNITY IN DOCUMENTATION

A BIBLICAL FRAMEWORK THAT INFORMS THE ETHICS OF PHOTOJOURNALISM

When combined, it is clear that words and images have the power to shift reality. Photojournalism is a tool that can bridge gaps with understanding, stir compassion, provoke movement, and transcend many barriers of presupposition or ignorance. Though it is effective in being informative, it is not often ethically or biblically operated in. The Bible is present evidence that God values using detailed written documentation, and evidence that accounts can be dignifying. The scriptures are exactly this; showcasing His interaction with His people throughout history to tell the world of His love, both beautiful and ugly, but never at the expense of the subject’s dignity. It’s essential for the Christian photojournalist to use this reference to directly inform the practicalities of their work. If this effort is neglected, it’s possible that photojournalists will not only continue on dishonoring God as they dishonor his people, which is seen to be the primary offense, but additionally wound individuals on site. A properly developed theology of dignifying in documentation is a necessary foundation for any user of the camera, particularly in ministry.

Dignity as defined by Merriam Webster is “the quality or state of being worthy, honored, or esteemed”, and it is important to consider how the study of God and His word informs what it means to dignify the individual in this field. Aspects of this claim that are necessary to consider include how the Imago Dei informs the foundations of this standard, biblical accounts that demonstrate documentation that dignifies, as well as the practicalities that form out of these theories.

The Imago Dei Demands Honor

The base of this claim is a derivative of the Latin ‘Imago Dei’, the innate “image of God” in mankind. This is what gives man dignity and demands he be treated as such. Biblical perspectives would define dignity as a state of being worthy of honor or respect due to their inseparable likeness of God in nature. Our basis of this understanding comes from Genesis 1:27 that shows us this connection in stating “So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them”. The God who is to be upheld with the most reverence and honor created mankind in his very likeness, and orders that man also be honored. God values them so much that he placed his very likeness in their form, so they should therefore be dignified. Man again is reminded of the principle in Romans 12:10 that explicitly commands humanity to honor one another by stating “Be devoted to one another in love. Honor one another above yourselves.” It is even a biblical mandate that man honor those next to him, and the love that can be shown through this honoring is evidence of Christ. This is our baseline.

Innate Dignifying Capability

All humanity has an innate desire to dignify and be dignified. Even man that does not recognize God is capable of this because he was designed after a God whose character embodies that trait. One does not need to know Christ to have a sense of what it means to dignify the individual. Mankind’s ability to recognize truth and live into it to a certain degree is the direct effect of their being made in the image of God, a likeness in function, that defines dignity and honor. There is an inescapable reflection of the creator in man that was designed to both be dignified, and dignify, so all potential subjects have a sense of the sort of treatment they are designed for.

Danger of Selective Portrayal

Photojournalism should be relational, and an interaction that demands the community being documented is perceived as a people over a content. The lense should never be a tool of divisiveness between the subject and the photographer, but rather a means of bridging gaps by sharing understanding. There are certain principles that must be held to maintain this disposition, and all come back to the idea that what the photojournalist selects to portray about a person matters deeply. It suggests to the world that that feature is what they are.

Circumstance

It is a standard that photojournalists communicate the essence of the subject’s holistic personhood through what they create. Though it is certain that only selective information will be shared about an individual, what is selected to document must inform the viewer of the subjects full personhood. Photographers have the power to project a perceived identity onto their subject, and this is determined by what they choose to highlight in the image they create of their subject. The danger in this is that a subject can be portrayed to be something that is very unrepresentative of their holistic personhood or circumstances. The imagery should document from the angle that suggests they are an individual experiencing their circumstances, but not identify them with that circumstance. Of course this is difficult to do visually, but very possible. An unfortunately popular example of this misuse in documentation is how the poor or vulnerable are visually represented. For example, an image of a man experiencing poverty should be just that. The image should primarily highlight that he is a human, and secondarily, if at all, depict something he is experiencing. Their photographs can be taken in such a way that portray them to be nothing more than their poverty, and take into account no additional details apart from their unlikely circumstances. It does not suggest they are an individual experiencing poverty or homelessness, but says that they themselves are identified as poor or homeless, and nothing more. The typical image brings attention to details such as uncleanliness, isolation, or desperation and seems to communicate that there is nothing more to know about them. Many might believe they are doing a service to portray the reality of the suffering, but it is critical to consider whether the reality is even something to be documented. We unfortunately tend to mass consume this as a form of entertainment, and rarely something that provokes action.

This is especially dangerous when considering profit. Imagery motivated by money is a very sensitive matter, and can morph the documenting into an exploitative act. It is possible for the subject to no longer be viewed as a human being, but a source of income. The documenter is seeking to gain from portraying what another lacks. Sharing the story of someone who has little can not be told for the sake of it, and can never be motivated by marketing strategies to provoke empathy that provide proceeds. An article covers the unethical use of excellent design in this context, and speaks of the damage it entails.

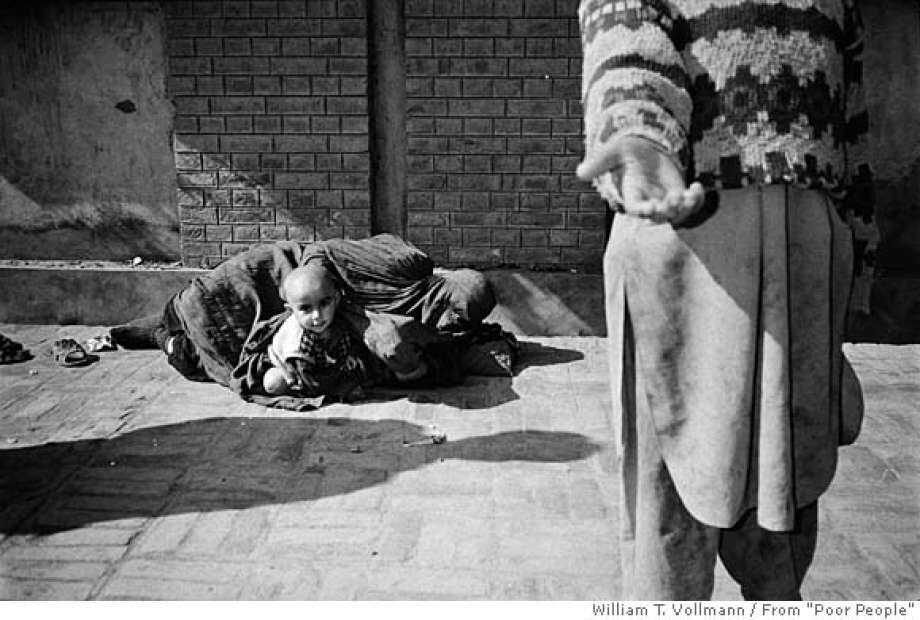

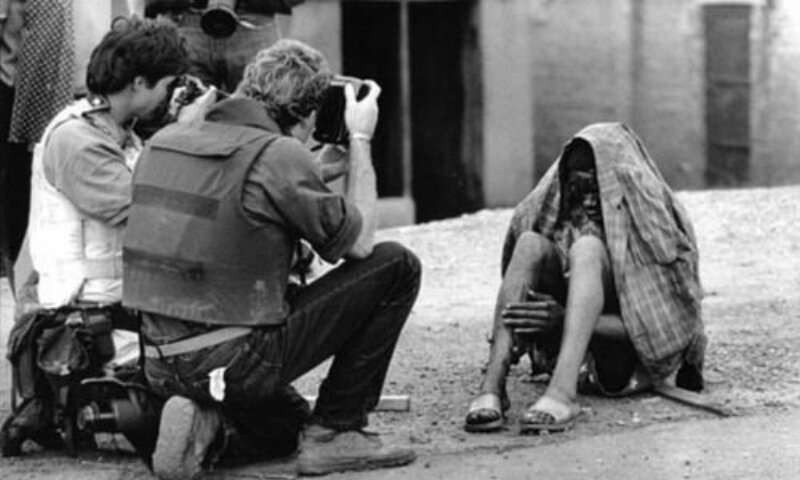

Here are some examples of this misuse:

On the left, you see an exploitation of the poor to manipulatively provoke the necessary sympathy to increase donations for a given cause. It is an objectification of people experiencing poverty to startle a privileged audience and produce the desired outcome for the charity. On the right, you sense the invasive nature of these photojournalist’s documenting process. The subject seems to be feened over as content, provoking shame and building barriers. It’s important to consider how the extreme alternative of portraying the wealthy to be nothing more than their wealth is neither an honorable act. To emphasize their luxury or designer possessions above their thoughts, feelings, or accounts of experience is a disservice. This side is often glorified, rather than pitied, and that sends a message about societal values in itself. Within the boundaries to what is honorable to document, there are a variety of ways one can highlight a personhood over a circumstance.

Holistic Personhood

As mentioned, it is necessary to recognize someone in their full personhood. This can be done through taking into account their experiences, thoughts, and emotions through additives such as quotes, close proximity, or a focus on the subject’s face over what surrounds them. In addition to the use of these methods, it is critical that photojournalist’s interpret all people as a neighbor to consider, not an ‘other’ to passively observe. Quotes invite a reader into a personal experience and eliminate some danger in misrepresentation, because the subject has the liberty to choose how they represent themselves. It is not wrong to simply use a photograph of someone without the addition of a quote, but if it is being written about, I strongly believe they should have the first seat in giving an account. After all, it’s their face and their experience, isn’t it? If it is difficult to highlight the person over their context, close frame shots are more intimate and tend to speak loudly about personhood. Close proximity with the camera can also play a role in making distinct the subject’s common humanity, and work against the potential of being portrayed as a specimen to be observed. A far shot can give a sense of separation that leads to the subject being perceived as other, and the perceived distance can work as a barrier. If possible, a focus on the subject’s face in portraiture invites the viewer to level with them and distract from the notion of ‘other’.

Sexuality

An element falsely glorified in most mainstream imagery is the over-sexualization of a human. To elevate an individual’s sexuality in any sort of photography suggests that their sexuality is what is primarily worth being highlighted in them, which certainly does not honor, but degrades. This is a norm of culture today that can not be passively adopted in the field. It is very exploitative to expose the sexuality of anyone, but certainly unacceptable for a child. If they are naked in their circumstance, there is no license to document.

Truthful Documentation

Unbiased honesty in storytelling must be fought for. Exaggeration or altering reality for a greater effect is a great threat to journalism. Though reality may be an interpretive concept, there is still a degree to which one can commit themselves to truthfulness in this sort of work. At times, truthfulness may mean communicating information that someone might not be proud of, but in a way that make value claims or exploit for entertainment. The Bible is the greatest example of what it means to document in a manner that is in accordance with God’s heart, and readers will quickly see that this does not mean withholding from documenting what is ugly. It is simply a part of the story.

Thomas’s disbelief in Jesus’ reappearance in the book of John is a perfect example. It is not only valuable to consider what is documented in this story, but equally as much as how. Thomas is told by the remaining disciples that Jesus has returned in John 20:24-29, and scripture records his blatant disbelief. When he sees Jesus face to face, he acknowledges the truth in reverence. Scripture could have withheld from showcasing such a shameful act from Thomas and carried on to the time where He believed, but there can be much value in documenting portions of stories that maybe the subject would not advertise about themselves, but in a manner that greatly maintains the subject’s dignity.

An additional example to consider in scripture is the story of David and Bathsheba in 2 Samuel 11, a deeply unlawful act taking place. The king essentially kidnaps a woman he can see atop his home, demands sexual relations with her, and murders her husband. This is of the more detrimentally shameful decisions in scripture, but never does it’s account attempt to strip dignity from David. There are no value judgements, gossip undertones, or slander against him. The wretchedness of the story is acknowledged in verse 27, and gives the understanding that it is not condoned. 2 Samuel 11: 27 writes “But the thing that David had done displeased the LORD”.

This shows readers that to dignify a subject being documented doesn’t mean to cover exclusively what they are proud of, but to withhold from any slanderous, dishonest, or exaggerated tones in the account of even what was destructive.

Posture

What to document is equally as valuable as the posture that the photojournalist documents out of. One must examine the posture out of which they are documenting.

Bias Removal

It should be noted that most all of the highly regarded photojournalist organizations in the world are based out of western society. For example, stories from the New York Times or Time Magazine are some of the most widely viewed content in the world, and it is possible that the most popular images of the world are perceived through western civilization. In light of this, it is critical that they find a way to counteract documenting all people out of that pervasive western bias. A photojournalist must step out of their own context and into the subject’s to be able to rightly love them. An acknowledgement and respect of the idea that there are other ways of living and thinking about reality is vital. Something the photographer from western civilization must implement to counteract this issue is first a recognition of the ‘others’ perception of reality as distinctive from their own, and additionally an effort to adopt that understanding of reality while subsiding the idea that their own may be superior. This can be done through humble observation and intentional asking.

Through her missions, a famous photojournalist with New York Times, Linsey Addario, demonstrates the importance of knowing and being trusted by a people, because that is what allows an honest and honoring depiction of their nation. It’s quite impossible to tell of a group truthfully without even attempting to understand their context or sit with them in it. It is a dangerous move to manipulate the stories you tell into a mold that has been formed by a bias, especially if that bias is governed by national policies. Linsey writes “Afghanistan was much more than a terrorist state governed by unruly women hating Taliban, as much of the media portrayed it.”(55). It took an intentional sitting within that context to view it as otherwise. It is critical to humanize these people, and build the bridge that allows others to understand the depths of pain people similar to them call their reality.

Photojournalists must additionally consider how the primary user of the camera being based out of western civilization affects the bias that most eastern cultures have towards the use of that tool. It is possible that in a photojournalist’s interactions, the association with the tool of the camera being used is, for them, tied to divisiveness, misrepresentation, and dishonor. This is something to be mindful of, and could even differ some of the work intended to be done. It’s important that the documenter invites this sort of instance to be an opportunity for healing, or will respectfully withdraw as a response. The greatest way to grasp another community or culture’s perception of reality is to spend time living alongside them within it. Asking the people in that space what they value most and why aids your capability to highlight what is truly meaningful to them. Simply watch how they interact and dignify each other. Is it primarily through service? Honor? This deep understanding can never be some sort of mere cognitive transfer, an exchanging of information, but must be lived into in a sharing of intimate space. This can also work as a preventative time that protects the photojournalist from severely dishonoring a community without realizing or intending. The time a photojournalist spends alongside can highlight the things that are sacred or private, and prevent any misunderstandings that can morph into hurting a community. For example, there is a community in Chamula, Mexico who believes that their soul is robbed if a photograph is taken of them. Without context, a messenger of the gospel could be deeply rejected and pained by their ignorance to what is sacred to those people.

Listening

Before anything, you must be a humble listener. The documenter is a learner, and is seeking to grasp anything they can about the community’s ways of life. This concept might first bring to mind an international context, but we can’t forget how many varying sub-culture nuances there are in this country alone. For instance, in some cultures sharing is a sign of honor, and if you trust them to know of you, your vulnerability honors theirs. When done humbly, this posture of listening in living alongside one another can produce a mutual trust between the documenter and the documented. It enables a community to believe the documenter has a proper understanding of them, a desire to respect them, an interest in their personhood over their providing of content. That they haven’t only come to take, but to understand and give. Though there isn’t always an opportunity to have an extensive period of living alongside any foreigners. If the case requires a very back to back entrance and exit, discernment is key in the decision making process. In this instance it is important to consider if the community has a pre-established trust with whom has sent the photojournalist or any of those they’re working with. Additionally consider if anyone sending the photojournalist is familiar with the community in which they are going, so they may prepare and train that person prior to departure. If there are no pre-established connections or understandings, the photojournalist should spend a designated amount of time seeking to know and love the people before the camera is ever introduced to the setting.

Reconsider

The Imago Dei is the foundation of this work as it suggests man is dignified, and innately demands he be treated as such. Man’s dignity can not be taken, but he may be portrayed in such a way through documentation that is not reflective of the truth of him being worthy of such. There are unfortunately ways that this dignity can be dishonored through methods of documentation, including selective portrayal in circumstances or personhood. The basis is that the humanity of a subject in any sort of documentation should be greatly elevated above their experience, sexuality, context, etc. It is important to combat these un-dignifying means of documentation by representing reality truthfully out of a posture of humble listening and unbiased efforts. This tool has the power to bring unity with compassion and understanding that sparks movement, or become a means of divisiveness in misrepresentation in postures of consumeristic superiority.

This standard of ethics can never be a fear based method driven by self protection, but an honest effort to honor the individual. It should be understood that not all stories are meant to be told, but immense intentionality should guide those that are. The basis of this information can be systematized, but all that gives life to this framework is deeply contextual. This is simply an ethical foundation for documentary content to be filtered through, and built off of. It is unacceptable for any photojournalist to go into the field without a concrete understanding of the threats introduced from a passive participation in this kind of work.